This review was originally published on the Learning Counsel website.

12-word description of app/product:

A reading program that provides intervention for students from 4th grade through adults.

Formats:

Online software

Website:

What does it help with?

Students who are struggling to read past the 3rd-grade level need deeper intervention. The Reading Horizons Elevate® Software assesses student needs, provides targeted instruction, and monitors student progress. Students learn how to read effectively through an explicit, systematic, phonics-based approach that uses Orton-Gillingham principles of instruction.

What grade and age range?

4th grade and above, including adults

Is this core/supplemental/special needs/extracurricular/professional development or what?

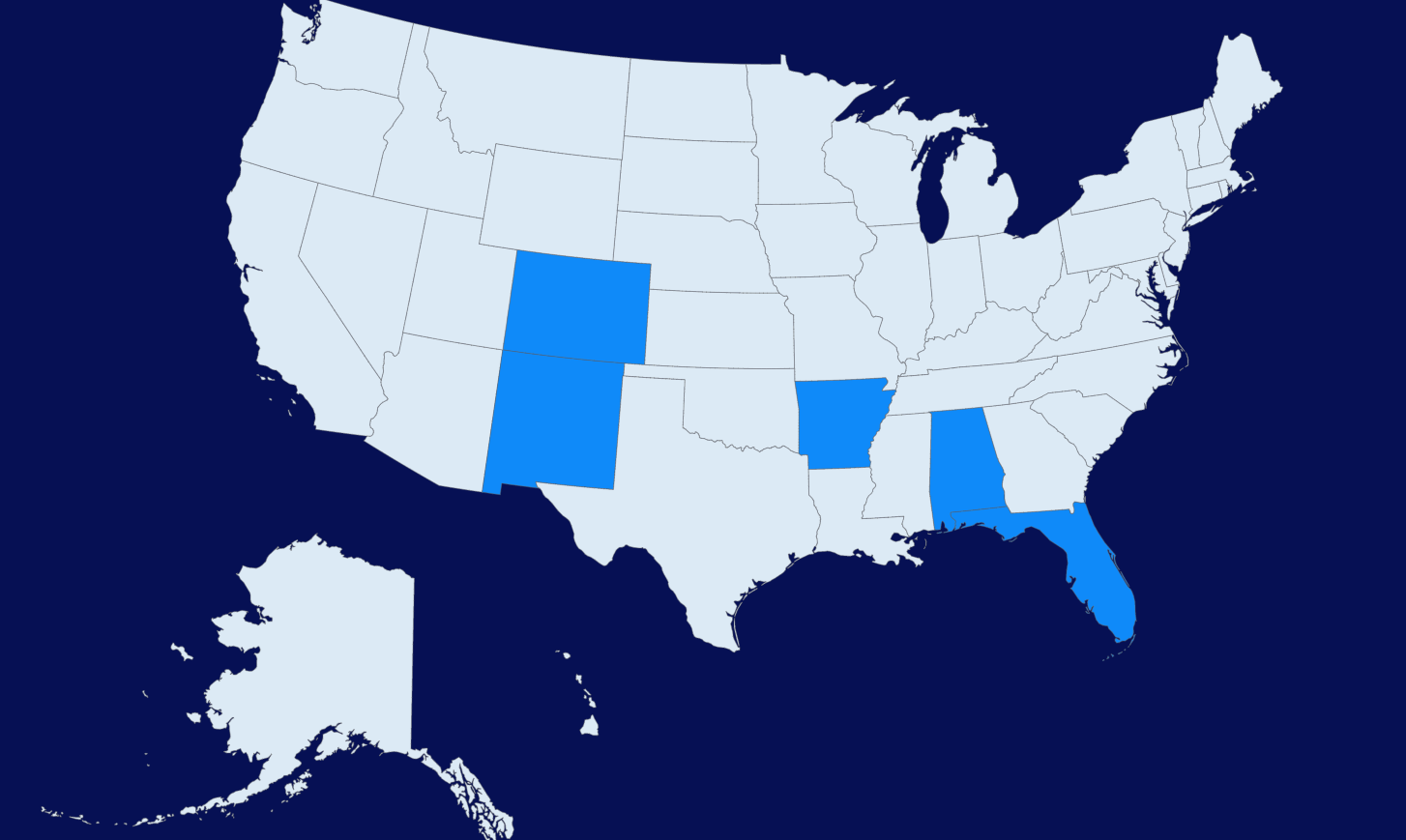

The Reading Horizons Elevate® Software is used as a reading intervention for struggling readers, students with special needs, and English Language Learners.

What subject, topic, what standards is it mapped to?

Literacy

What lesson time does it use?

Each lesson on the Reading Horizons Elevate® Software can be completed in 10–20 minutes. Because the software can be accessed by students at home, lessons can be completed during class time or assigned as homework.

What is the pricing model?

Because each school and district has diverse needs and capacities, pricing is specific to product needs and school or district size. Interested parties can contact an account representative at (800) 333-0054 for pricing information that is catered to specific needs.

Are there services around it?

Unlimited Tech Support

Each of Reading Horizons products are backed with free, unlimited tech support through phone conferencing and online resources.

Reading Horizons Accelerate® Customer Website

The Reading Horizons Accelerate® website is another free resource for customers that helps teachers prioritize student needs by compounding student data from the Reading Horizons Elevate® Software and dividing students into groups based on current skill mastery. Student groupings are recalculated for each skill students complete in the software, helping teachers determine how to best spend class time. The Accelerate website also connects teachers to how-to videos and lesson supports that can be used to supplement and enhance software lessons.

Teacher Training

When first implementing Reading Horizons products in the classroom, most schools select to have a one-day live onboarding training for their teachers and additional training through the Reading Horizons Online Professional Development Course.

What makes Reading Horizons unique?

Reading Horizons empowers teachers with the tools and training to target the specific gaps in each student’s reading skills—leading to efficient gains in intervention settings. When students master the skills taught in the Reading Horizons instructional method, they are prepared with the phonetic and decoding skills needed to read the majority of the words in the English language. Students learn these skills through a unique, research-based approach that uses Orton-Gillingham principles of instruction.

A description of the characteristics–how is it designed for user interface, user experience? What instructional design principles are at work here?

The Reading Horizons Elevate® Software was designed with older students in mind. It uses a modern interface, a simple reward system, and robust assessments to assure lesson content is suited to a student’s current skill level. Through this software, older students can fill the gaps in their foundational reading skills without wasting time learning concepts they already know and without the childish games and books that are often used to teach basic skills. Students maintain their dignity and independence as they master foundational reading skills, enhance their vocabulary, and transfer these skills into fluent reading with reading passages that appeal to older students.

Teacher reviews:

C. initially was placed in Reading Horizons Elevate in April of 2018. He struggled with reading and basic classroom rules. Because of his difficulty with behaviors, we took him out of the program for from June until August. Something clicked with C. and he came back into class motivated and wanting to learn. He quickly made progress in the program and having started at a 660 Lexile, he completed the program in October with a Lexile of 790. He improved in classes as well. On his vocabulary tests, he regularly scored 70% or below, with a modified vocabulary list. Toward the end of the Reading Horizons program, he began to score 90% or more on each test with no modifications. His comprehension improved in not only Literature, but in Science and Social Studies as well, causing his grades to improve. C. is in the middle of his 9th-grade year and has already made impressive gains. He reports that he thinks he will be ‘ahead of the game’ when he returns to his regular school.

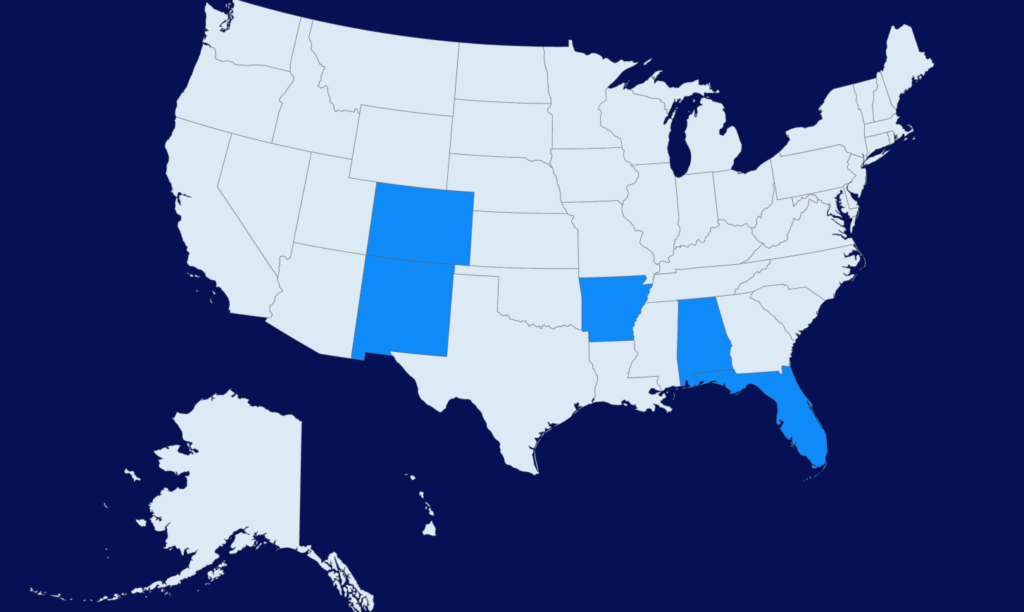

—Stefanie Harris, Teacher, Wyoming Boys School, WY

I placed an ESL student on the Reading Horizons Elevate Software program whose mother language is Arabic. Within just three months, his ESL level rose by a level and a half!

—Sara Chlebik, Northwest Service Cooperative, MN

More than half of my first group of students were able to successfully leave the program after three months of working with Reading Horizons Elevate, reading fluently on grade level and meeting their projected goal on a state-mandated test. This has allowed me space and opportunity to work with more students in need of this great program.

—Patricia McNair, Senior Reading Advisor, Shelby County Schools, TN

The upper-grade students are feeling successful with the Reading Horizons Elevate Software program and they see good improvement with their comprehension. They really like the library. They like the program because when they fail a quiz they can relearn and retake the test. They feel determined and successful when they take it over and finally pass. They like that lessons can be reset and redone. They ask for help more and more as the lessons go on. I like this program. It is working.

—Travis Lyons, Teacher, Carle’ Continuation School, CA

Keeping a student with an individualized education program on track during distance learning, all while combating the traditional summer slide, is challenging. A

Keeping a student with an individualized education program on track during distance learning, all while combating the traditional summer slide, is challenging. A