Have you heard the buzz around the science of reading (SoR) lately? Actually, it’s less of a buzz for many of us and more like the roar emanated by a turbo jet. There’s no literacy talk without the mention of the SoR because something fantastic has been unearthed, unveiled, and presented to all of us in literacy education.

As a teacher, just the thought of implementing SoR in the classroom could very well be overwhelming! You’ve probably asked yourself, do I throw all of this old stuff out? Do I keep these pieces and discard the others? What is important to have in my classroom if I want to implement SoR-based teaching with my students? Heads are spinning, we know.

Just like a business, a garden, or a camping trip, there are things you must have to function and yield the best outcomes. Let’s talk about the must-haves for creating a science of reading classroom!

10 must-haves for your

Science of Reading Classroom

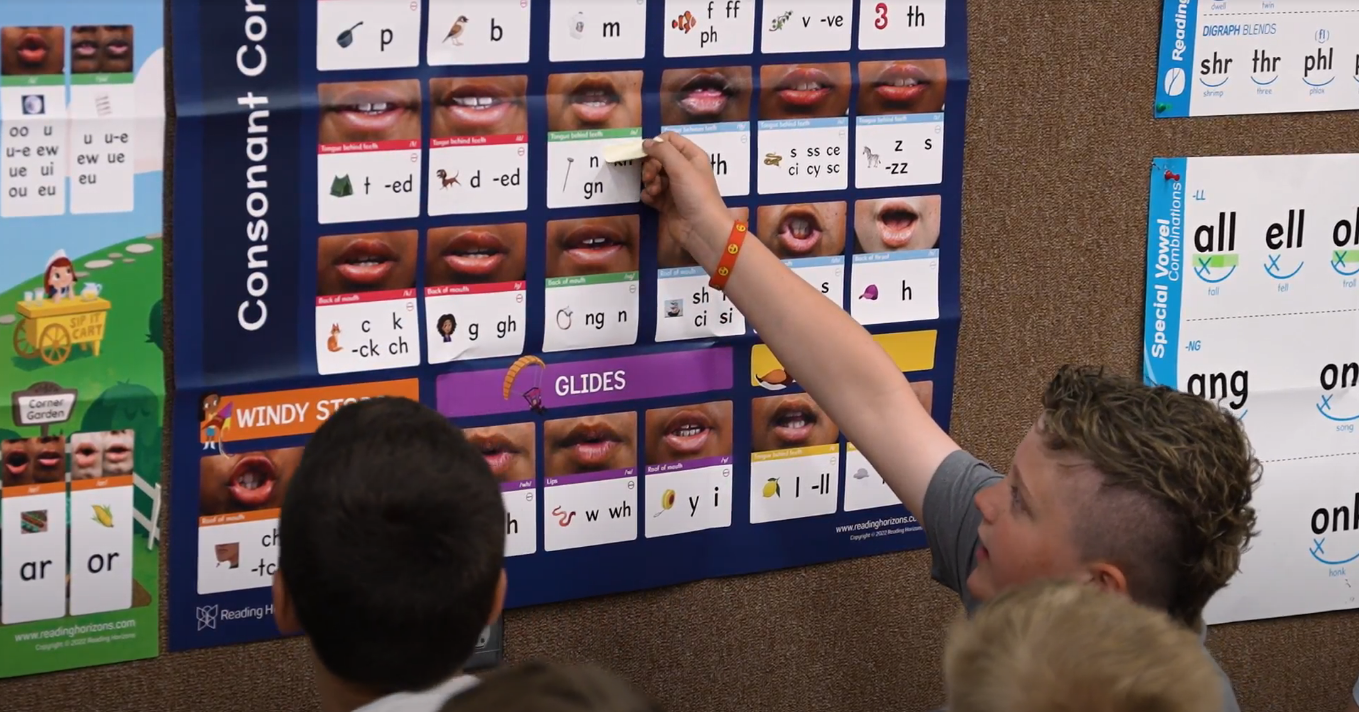

Sound Walls

If you teach K–3, you are in the crux of those “learning to read” years. To be successful decoders, students must learn and master the 44 phonemes (sounds) of the English language. Sound walls help students identify and understand the sounds they should be producing. I once had a student ask how to spell the word think. I suggested they check the word wall, but the student couldn’t find the word because they were unsure of the letters that represented the /th/ sound. Word walls only work to support students if they already know how to read the word. Sound walls include pictures of what lip and tongue placement looks like. Now when I get to observe classrooms using Reading Horizons Discovery Sound City™, I watch how the students focus on the sounds and articulation of what they are trying to spell and then go to the Sound Wall to confirm how to spell the sound. So when a student wants to write the word think, they start by saying the word, identifying the /th/ sound, and then looking to the Sound Wall to identify that it is t-h that produces that sound.

Mirrors

To springboard off the sound wall, students will absolutely need to have access to mirrors so they can see their own articulatory gestures when making the sounds. It’s helpful for each student to have a small, compact mirror available during phonemic awareness instruction. As the teacher explains the lip and tongue movement, students will have the opportunity to check their own mouth and tongue placement to produce the phonemes!

Digital sound walls can be a great tool as students can use their device’s video and microphone to practice producing phonemes. Sound production can be recorded and shared with teachers for review.

Systematic Instruction

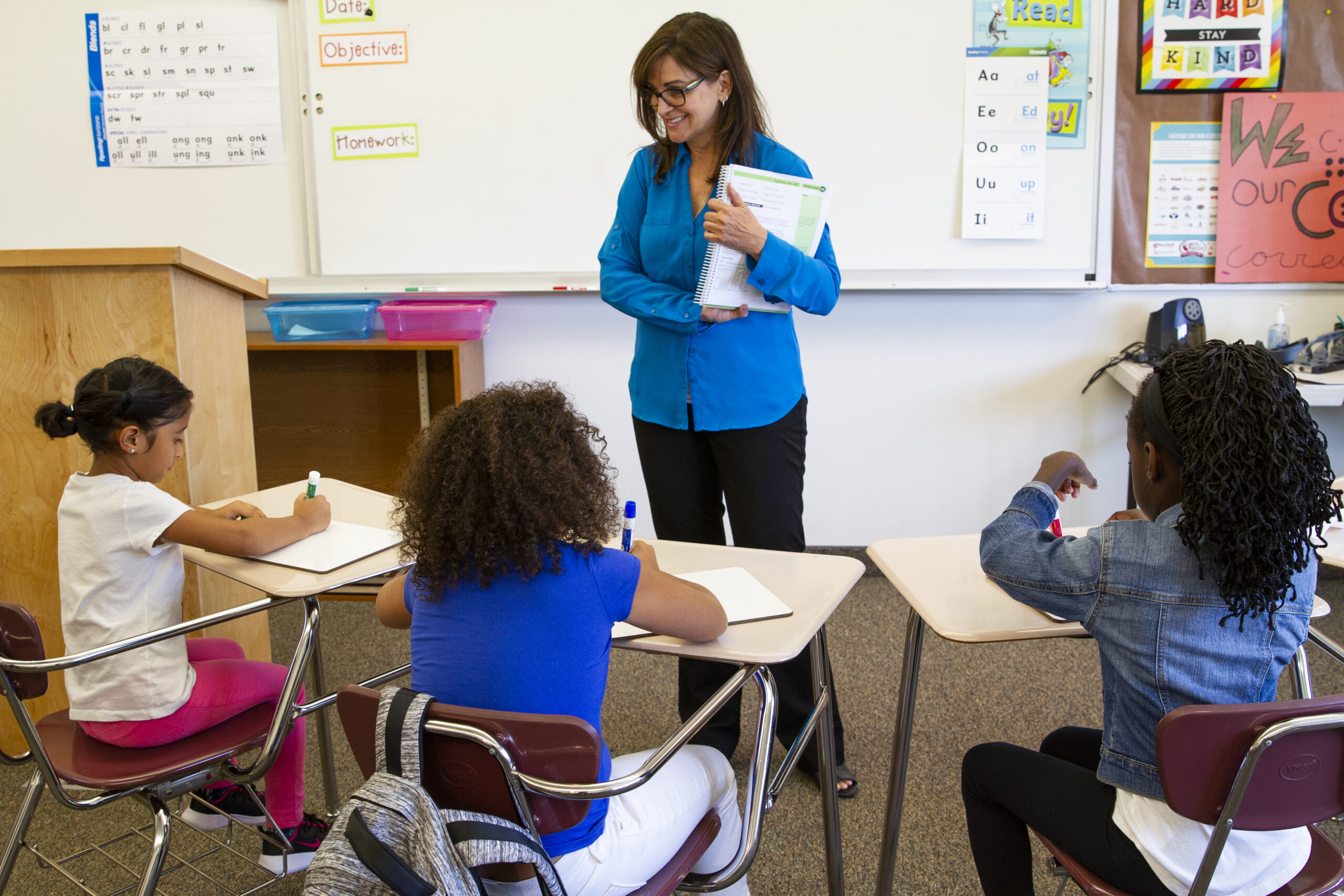

Using sound walls and mirrors is only as effective as the instruction that corresponds with it. When teaching phonemic awareness and phonics instruction, it is important to ensure the progression of every lesson is clear and systematic.

Systematic instruction follows a pattern like the gradual release of responsibility. One approach, coined by Dr. Anita Archer in the 1970s, was called “I do, we do, you do.” But, before anyone can move on to the next lesson, the teacher must ensure that students have mastered the previous foundational skills. Learning to read is a cumulative process that builds on itself. Have students prove they are ready for the next step. For example, if the new skill for the day is building CVC words, students must have mastered the alphabetic principle before attempting. David Kilpatrick described it as “…the insight that there is a direct connection between the sounds of spoken language and the letters in the written words.” Think about it this way: if you’ve never seen a measuring spoon or a mixer and only heard of an oven, would you be successful at baking a cake? Probably not. But, if someone took the time to help you understand how to measure ingredients and use the mixer and the oven, you might be able to create a scrumptious masterpiece! It’s the same with reading. We must teach the pieces before we teach the whole.

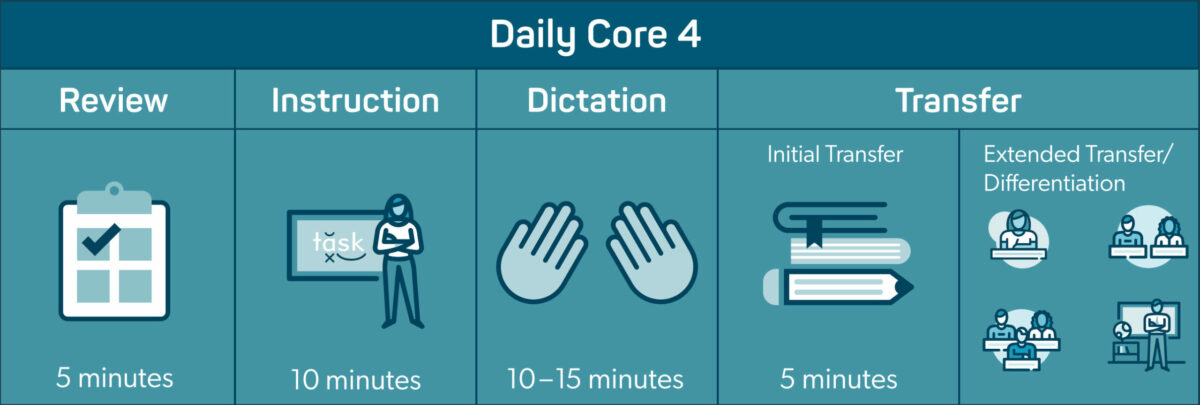

Once it’s determined that the students are ready for the new skill, use the gradual release of responsibility. Teach the lesson clearly and with precision. This is called explicit instruction, and it prevents the working memory from being overloaded. The “I do” portion should take about 10 minutes. Teach and model clearly to help the students understand, but try to have as little interaction with them as possible. This is listening and learning time for them.

Next comes the “we do.” This is a time for students to practice using the new skill they were taught. Let them practice on paper, whiteboards, your whiteboard, etc. This should take about 10–15 minutes. As they practice, walk around and give corrective feedback, positive reinforcement, and all the encouragement.

Finally, the birdies need to fly the nest so the teacher can see who has it down and who still needs some help. This is the “you do.” Have students prove to you that they can use the skill they learned and practiced. It is important to practice new skills in context. This can be choral reading and reading decodable books, and you can extend it into appropriate games for the skill, software activities, etc.

Decoding Strategies

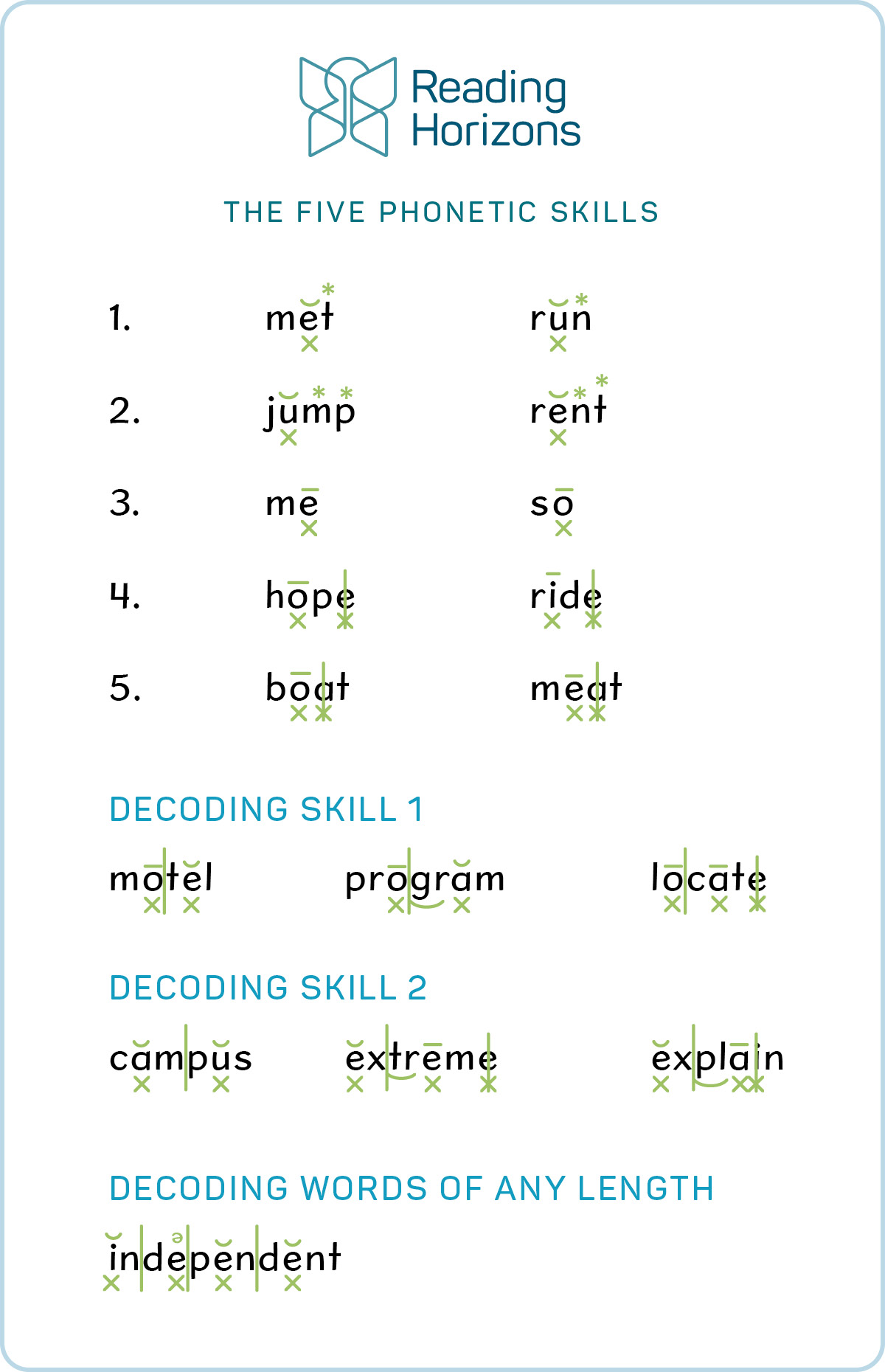

We can teach all of the comprehension strategies in the entire universe, but they won’t help a bit if students can’t read. Decoding is understanding a few patterns to unlock thousands of words, not memorizing four hundred words. When I was young, we’d get the best spelling lists during the holidays. I’d memorize words like turkey, family, snow, mitten, and sled. Why? I memorized it just enough to spell it on Friday, and then it slid out of my brain while I proceeded to enjoy the weekend. Decoding strategies help the brain understand patterns, and that’s what research has determined the brain always wants. Have you ever driven to work, and then thought, “Hmmm…I don’t remember driving over the bridge, but I guess I did!” That is your brain on patterns. It recognizes them, even when you don’t think you’re paying attention. The same is with words. If we teach students that when one or two consonants follows a vowel, the vowel becomes short, and the pattern unlocks thousands of words. If we only teach students to memorize, they’re missing out on a great skill! Reading Horizons teaches seven essential skills that you’ll want to teach students now: At Reading Horizons, we call these the Five Phonetic Skills and the Two Decoding Skills.

Here are the phonetic skills for single-syllable words:

- One consonant following a single vowel makes the vowel short.

- Two consonants following a single vowel makes the vowel short.

- A vowel that stands alone is long.

- Silent e at the end of a word makes the previous vowel long.

- When certain vowels are adjacent, the second vowel is silent, and the first vowel is long.

Here are the decoding skills for multisyllabic words:

- When there is just one consonant between two vowels, that consonant will move with the next syllable. Break the word before that consonant, and then decide which phonetic skill each syllable follows.

- When there are two consonants between two vowels, they will split. Break the word into syllables there, and then decide which phonetic skill each syllable follows.

There are more decoding strategies for students to learn, but these are some of the most important!

Encourage Orthographic Mapping

Orthographic mapping is what happens when the brain can automatically connect sounds to print. You can’t help but read something when this happens! Can you look at the words on this screen and tell yourself, “Don’t read that!”? Your brain already did it before you could get your command out. It was automatic. How can we practice this in the classroom? Hold up a picture of a cat. Have students isolate each phoneme while putting up a finger for each one: /c/ /a/ /t/. Then blend the sounds to pronounce the word cat. Using their papers or whiteboards, students then write the letters that represent the phonemes they heard. This practice of hearing the sounds and writing the letters that represent the sounds has been found through David Kilpatrick’s research to help permanently store words for immediate, effortless retrieval.

Decodable Readers/Passages

When I first learned the difference between leveled and decodable readers, I had to pick my jaw up off the ground. Decodable readers are usually 85–100 percent decodable based on what the student has been taught and has mastered. Again, reading instruction is cumulative, so, for example, if a student has just mastered L-blends, they can successfully read a book that only includes skills up until that point. We wouldn’t find the word phone in the book because the student hasn’t had exposure to the /ph/ digraph or the silent e. When I realized I’d been asking my emerging readers to decode words that had untaught skills in them, I nearly toppled over. No wonder we were struggling in our small groups!

Many different reading programs offer leveled readers, and more often than not, the same book is used all week long. Repetitive reading promotes memorization, which isn’t terrible, but why learn four hundred words when you can learn a skill to unlock a thousand? Leveled readers for small groups are often based on reading levels that represent where a student should be at based on grade level. If we were all pulled from the same mold, that might work, but that is not the way of the world.

What if you sat with a child who was reading a book that only had decoding skills in it that they’d been taught? What would you see when they finished reading? Excitement? Self-efficacy? Motivation? These are all things that come from setting students up for success by putting a decodable reader in their hands!

Hands Down/Hold-Ups

Dr. Anita Archer expressed her feelings against “raise your hand” in a Literacy Talks podcast episode. She said we all know the ones who raise their hand—the confident students, the students that aren’t shy, the students who don’t usually struggle. We’re wasting time raising hands when we should be doing “hold-ups.” Every student needs paper or, even better, a whiteboard and dry erase marker. That’s where we find answers to questions, and while we’re doing it, we can be giving effective and corrective feedback. If the teacher asks, “Who can spell the word kite?” after a lesson on silent e, it’s better to see the entire class answer than to see one student do it. Hold up, scan, take mental or physical notes, and move on.

Data to Save Time

Keep ongoing student data. When you’re in the “we do” portion of the lesson, check off who’s got it, who needs a little help, and who requires intense intervention. Knowing exactly what skills students are struggling with will help to quickly create small groups. Data tracking also helps to avoid reteaching something the student already knows. This is especially important with older students who are still emerging readers. They have a lot of foundational skills, but they have gaps. If we don’t pinpoint exactly what skills they’re struggling with, we might not be putting our efforts where they need to be.

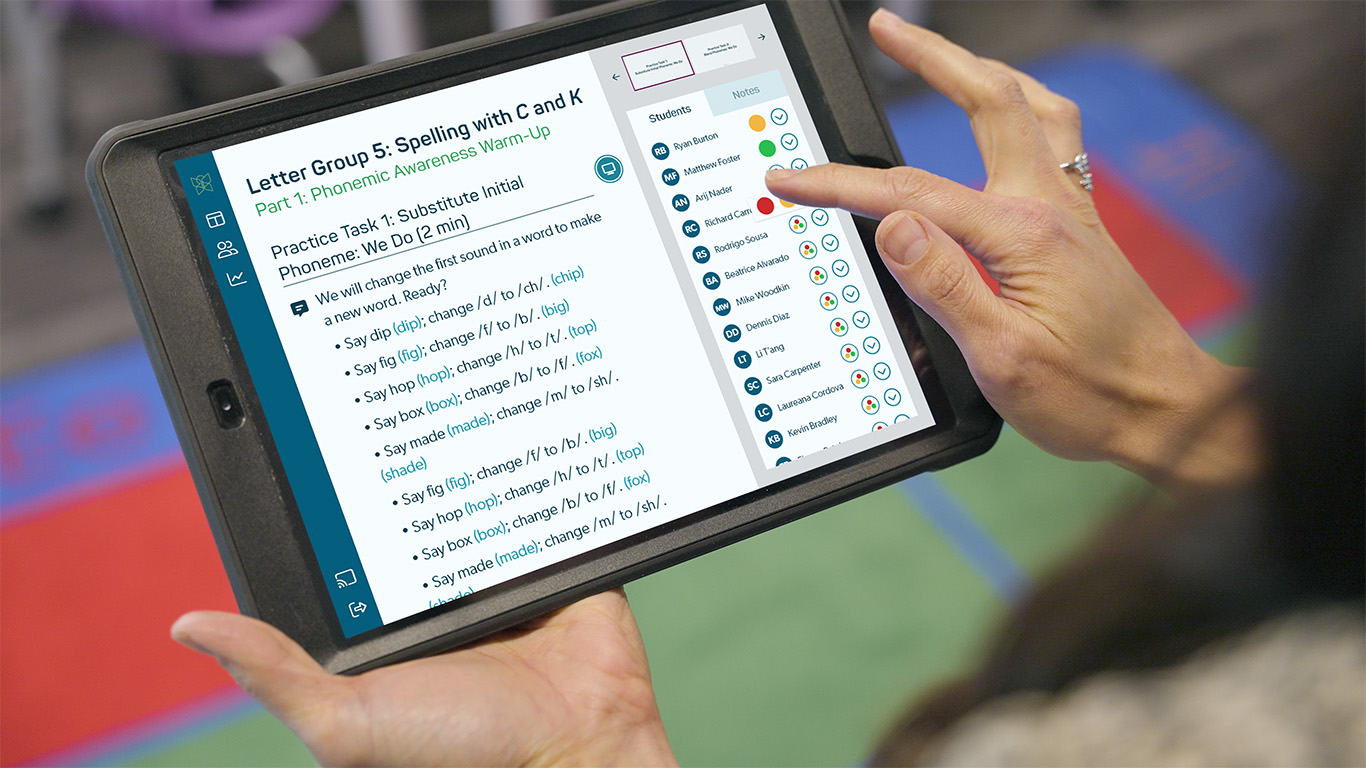

With a tap, Reading Horizons Discovery® opens up a world where your next lesson is cued up, student-specific practice is automatically synced, groups are sorted based on needs, and a data dashboard shows where the class stands at any given moment.

Get Moving!

A multisensory approach ensures that students maintain engagement and that all the necessary processors are being used in the brain so students can retain information faster. With a multisensory Dictation, we have covered all the processors in our brain that need to be engaged with the auditory, visual, phonological, and orthographic processors. During an accountable review or during the “we do,” have students stand, listen, repeat back, write, and read! All of these work together to trigger each part of the brain involved in accurate and fluent reading. Do all students learn by listening? No way! That is why Reading Horizons also uses hand motions to keep the body moving and creates cues for the student’s expectations. (Pic of 4-part processor w/link to dictation video?)

Positivity Pictures

A picture of each child with a caption of something they are really good at is probably the most important thing you can have in your classroom. Unfortunately, it is not widely understood that reading ability and intelligence are completely unrelated. Before your students even get a chance to think that learning to read is difficult, tell them their worth, and tell them what they’re good at. Dr. Sally Shaywitz explains in her book Overcoming Dyslexia, “… Every evaluator should take the time to visibly demonstrate to every tested child where his or her reading lies and then where, on the curve, his or her intelligence score lies. When this information comes from an objective authority figure rather than the student’s parents, it makes a powerful impact.” To the educator, the teacher, the interventionist, the paraprofessional, the principal: with all the energy and love you have, make sure the student understands their ability to decode has absolutely nothing to do with their level of intelligence.

So, what are you going to do tomorrow? Set up a sound wall? Make your lesson systematic? Let us know how you drove the science of reading into your classroom!

Jenny Kier is the Director of Education Specialists at Reading Horizons.