Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker said, “Children are wired for sound, but print is an optional accessory that must be painstakingly bolted on.”

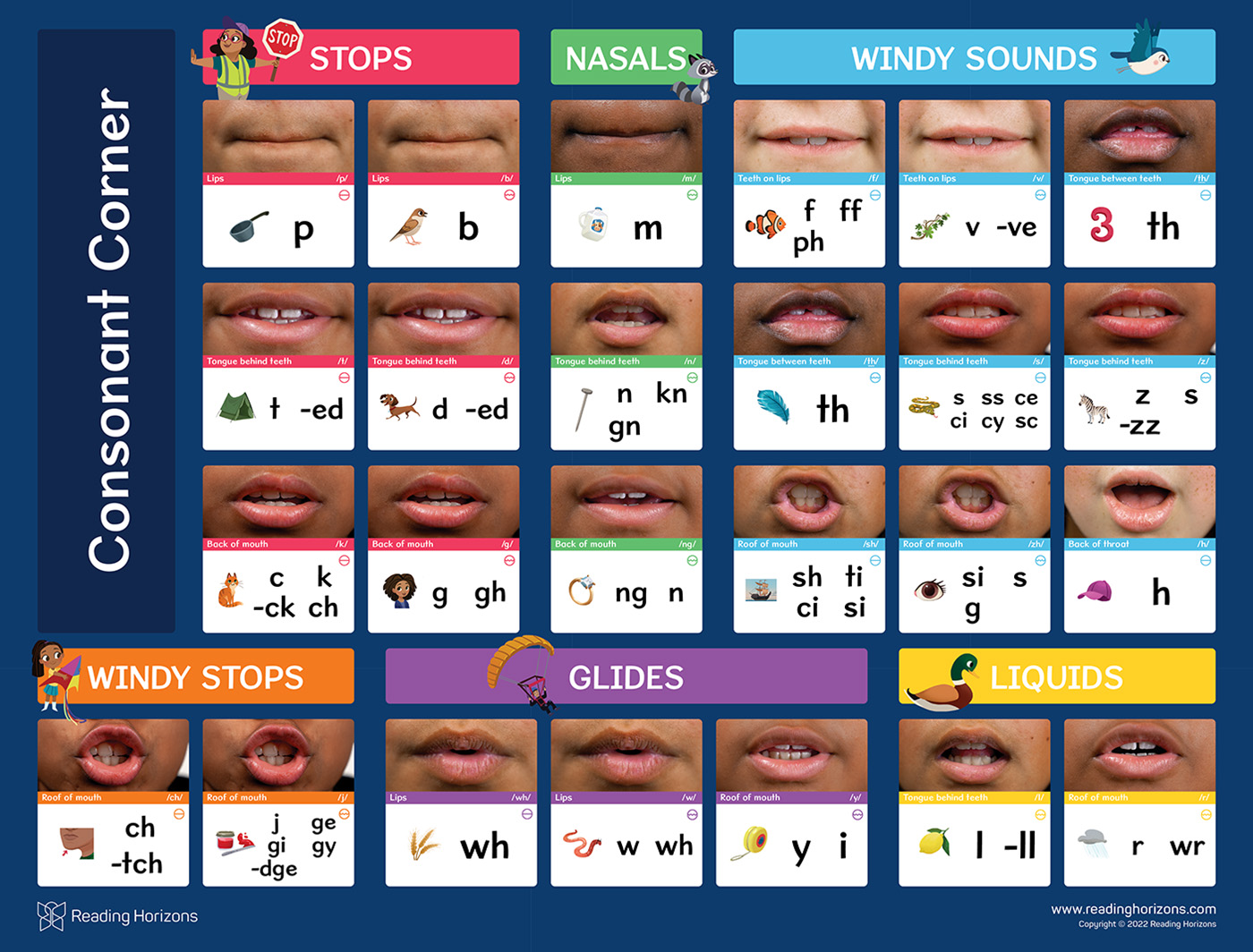

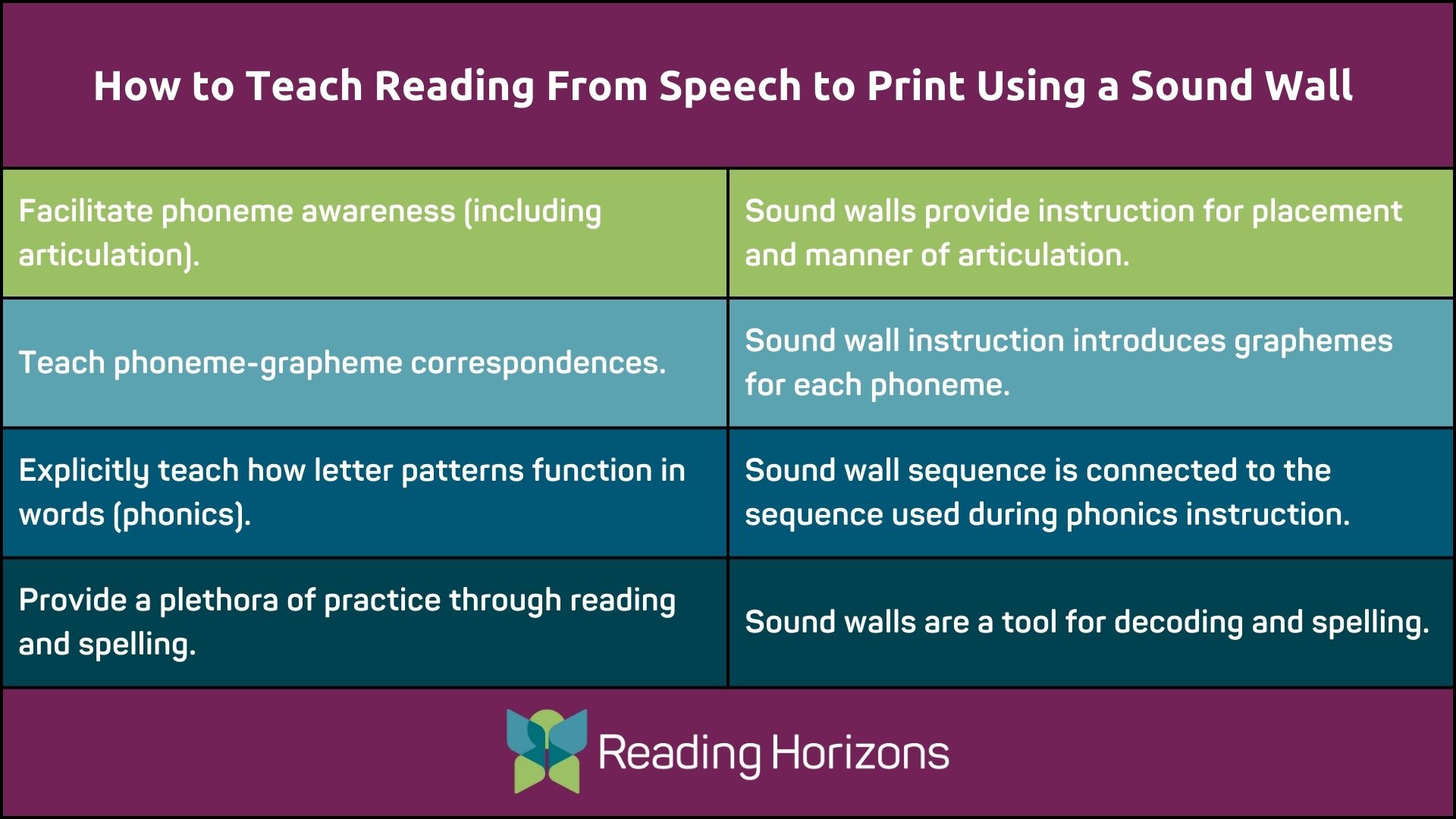

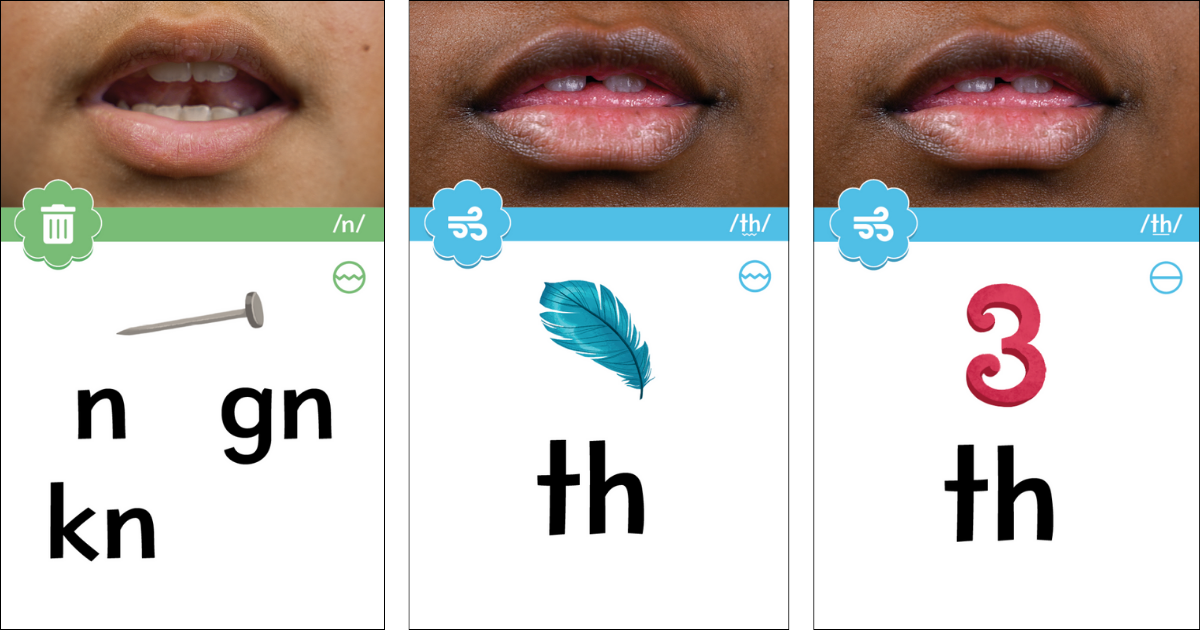

A lot goes into how people learn to read and how educators teach people to read. Teaching phonemic awareness among young and striving readers is a necessary first step, as learning to read moves from speech to print. Educators need to facilitate an awareness of speech sounds, then teach phoneme (sound) to grapheme (letters) correspondence and explicitly teach how those letter patterns function in words. At Reading Horizons, we directly instruct each phoneme and its corresponding grapheme as the foundation for phonics instruction. A key tool for teaching phonemes and their corresponding graphemes is a sound wall. Sound walls show the articulatory gestures of each letter sound in the English language and the letter or letters representing those sounds to create easy-to-implement instructions aligned with how a brain learns to read.

How Are Sound Walls Different from Word Walls?

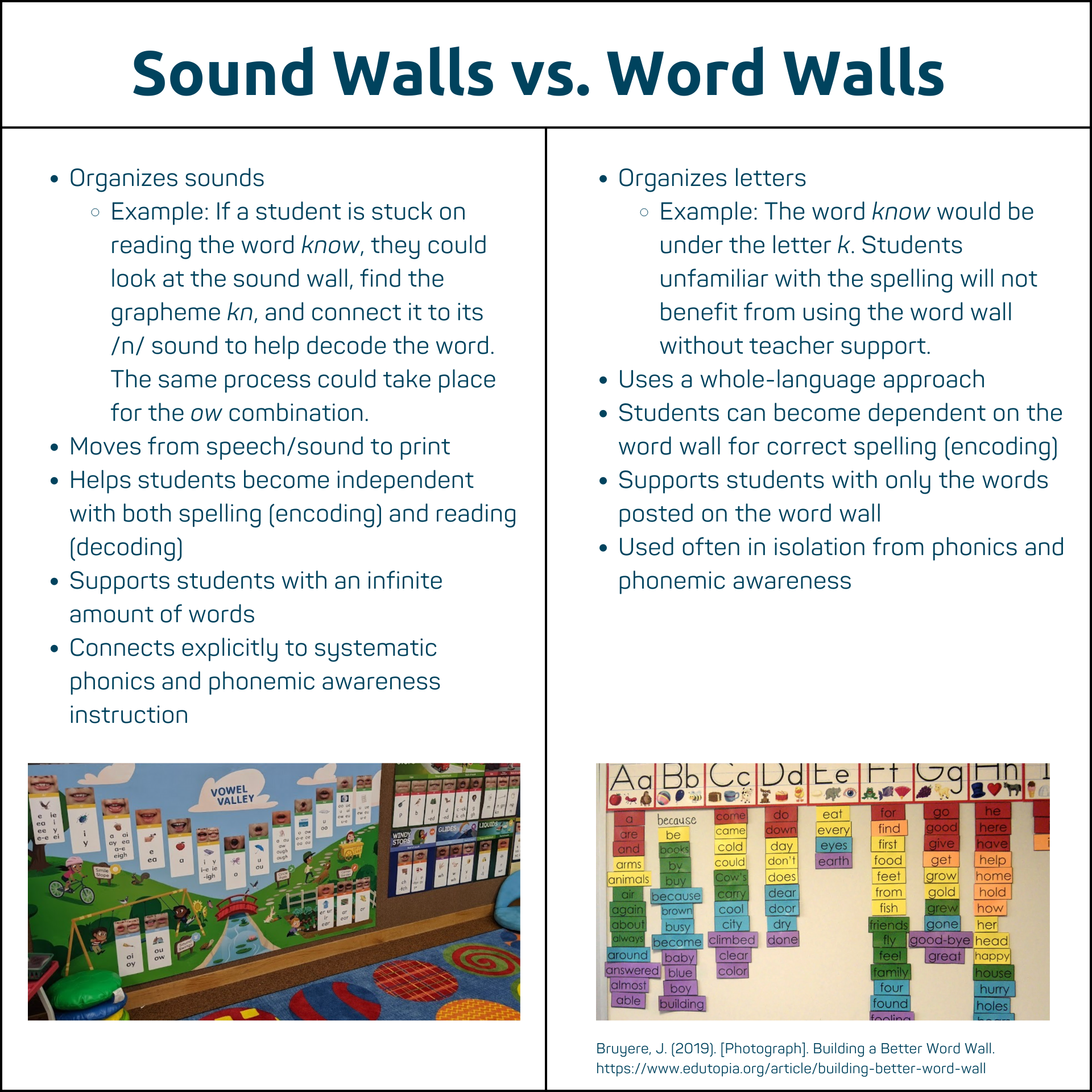

Most teachers are probably familiar with word walls. Each letter has a list of high-frequency words under it that students can see and familiarize themselves with. Word walls have limitations that sound walls don’t. Since proficient readers (educators) created word walls, letters are placed in alphabetical order, and the words under each letter start with that letter.

Students new to learning letters aren’t going to be aware that in a word like know, the /n/ sound is spelled with the letter k as the first letter. With word walls, students are tasked with memorizing words based on spelling, not sounds and the letters that spell them. So for a word like the, the student would spell the word t-h-e but need to know that th represents the /th/ sound, not the /t/ sound that they have learned t spells. It’s a print-to-speech approach, meaning students are required to memorize the word as a whole. Whole-word memorization interferes with what needs to happen in the brain for effortless decoding to take place.

When educators teach with a sound wall, they’re teaching each of the 44 sounds students will eventually be able to use to form and combine to read and spell an enormous number of words. In truth, they should be called sound-spelling walls. When practicing spelling and reading, students can turn to the classroom sound wall to find which phonemes are represented by the letters they are reading in a word. Conversely, if a student wants to know how to write the, they can look at the sound wall’s articular gestures to aid them in remembering that the spelling for the /th/ sound is t-h. This approach facilitates connections in the brain that help students efficiently map phonemes to the graphemes that spell them as they read. This cognitive process is referred to as orthographic mapping and is essential for the effortless decoding that is necessary for fluent reading comprehension—the aim of all reading instruction.

What Is a Digitized Classroom Sound Wall?

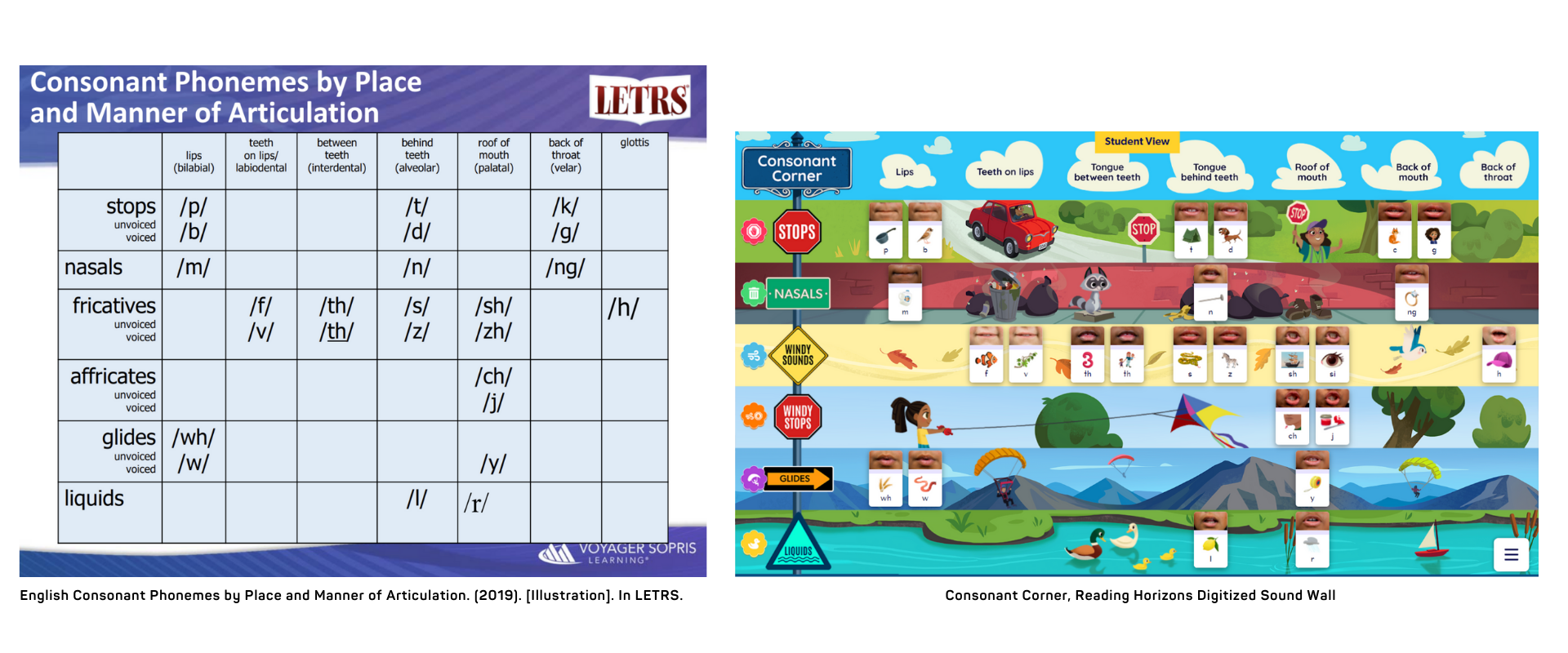

The 26 letters in the alphabet represent 44 sounds in over 250 spelling combinations. Sound walls help educators explicitly teach letter pattern functions without cognitively overwhelming students. Digital sound walls can be used as a tool to help educators teach the speech-to-print nature of reading development in an engaging and playful way. This includes facilitating phonemic awareness and providing articulation explanation examples for students. Classroom sound walls help educators introduce the most common grapheme for each phoneme. It’s a fun way for students to make connections between speech sounds and print.

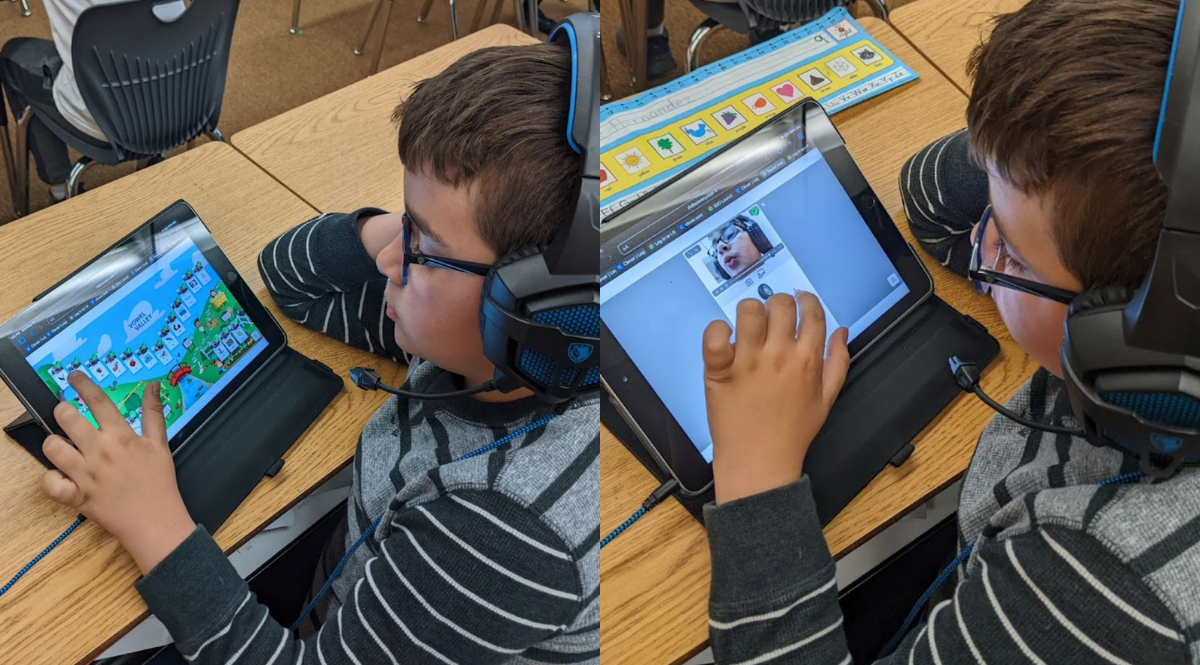

Digitizing your sound wall allows for direct instruction and opportunities for students to record themselves practicing letter sounds and send them to their teacher for approval. Once a teacher approves their submission, the student can replace the picture on the sound wall with their own picture. The software can also provide excellent learning opportunities for remote learning sound walls. Using software also provides students with endless opportunities not only to review what they have learned but also to master new patterns as they access the sound wall when reading and spelling.

Introducing Reading Horizons Discovery Sound City™

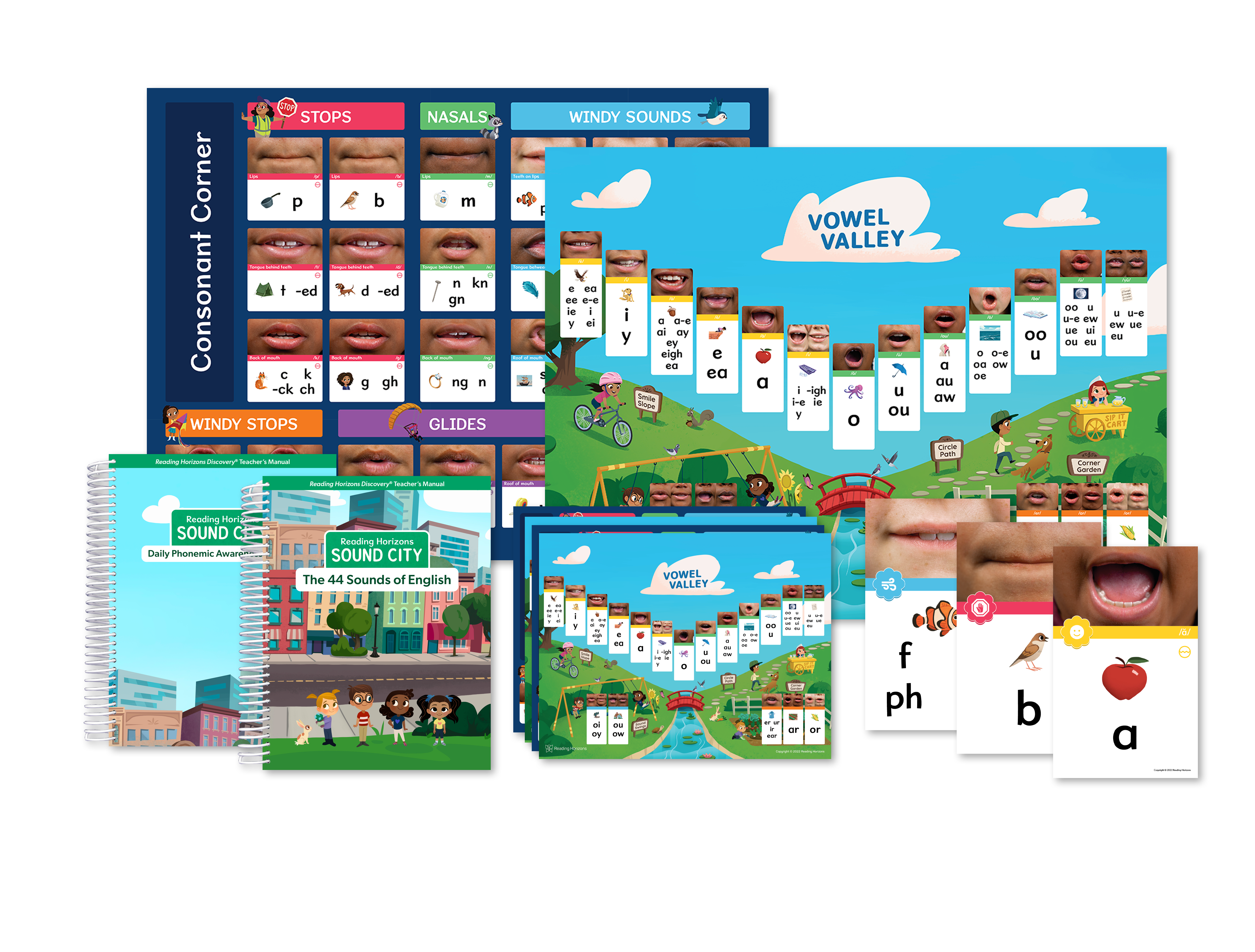

Reading Horizons has added Reading Horizons Discovery Sound City™ to our flagship solution, Reading Horizons Discovery®. The newly added component includes two teacher manuals, one for daily phonemic awareness exercises and one that offers direct instruction to teach the 44 phonemes of the English language and accompany the Reading Horizons Sound Wall. The digitized elementary Sound Wall included in Sound City allows students additional practice by guiding them through instruction and using a camera and microphone to record themselves making letter sounds, which they then submit to their teacher.

Sound City includes the following:

- Five-minute, daily phonemic awareness lessons that follow the gradual release of responsibility model and align with National Reading Panel recommendations

- 44 direct instruction lessons: one for each phoneme in the English language that aligns with Reading Horizons phonics lessons

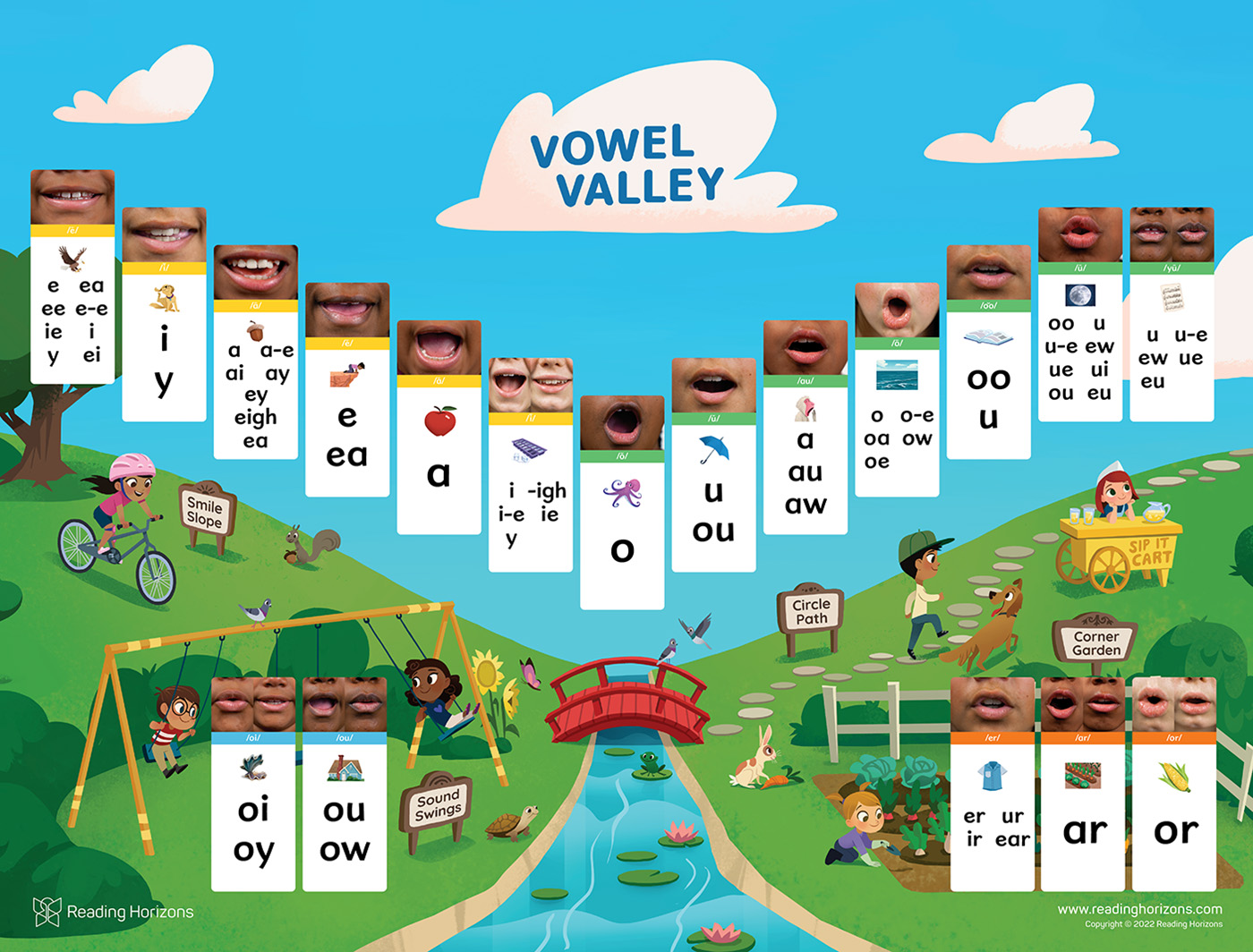

- Classroom instructional materials, including the Vowel Valley Poster, Consonant Corner Poster, portable sound wall cards, individual sound cards, and interactive sound wall software that allows students to record and photograph their own sound articulation to build personal digital sound walls

For educators who need some tips on how to make a sound wall bring phonics to life, Reading Horizons is hosting an upcoming webinar on the newly expanded Reading Horizons Discovery®.

What Sound Wall Instruction Looks Like

When incorporating sound wall instruction into their classroom, educators will intentionally flip instruction to start with the sound instead of starting with the letter and draw students’ attention to the articulation needed to produce the sound. In kindergarten, educators can do a sound a day to gradually introduce each sound.

Students who are familiar with phoneme-grapheme correspondences can, over time, efficiently store words in their long-term memory (Ehri 2014). When first introducing a new phoneme-grapheme connection, it is important to draw students’ awareness to the sound by discussing what is happening to the mouth to correctly articulate the sound and then connect the grapheme to the sound.

This approach is important because the brain recognizes speech through the vocal actions of the speaker and by the sound that is produced. This is important so that as readers become more proficient, their brains can fluidly recognize the difference between words that sound alike (e.g., fall, fill, fell). In this way, our instruction supports cognitive functions essential for writing and understanding written text.

Check out the video below to see how fricatives, or windy sounds, are taught using kid-friendly language.

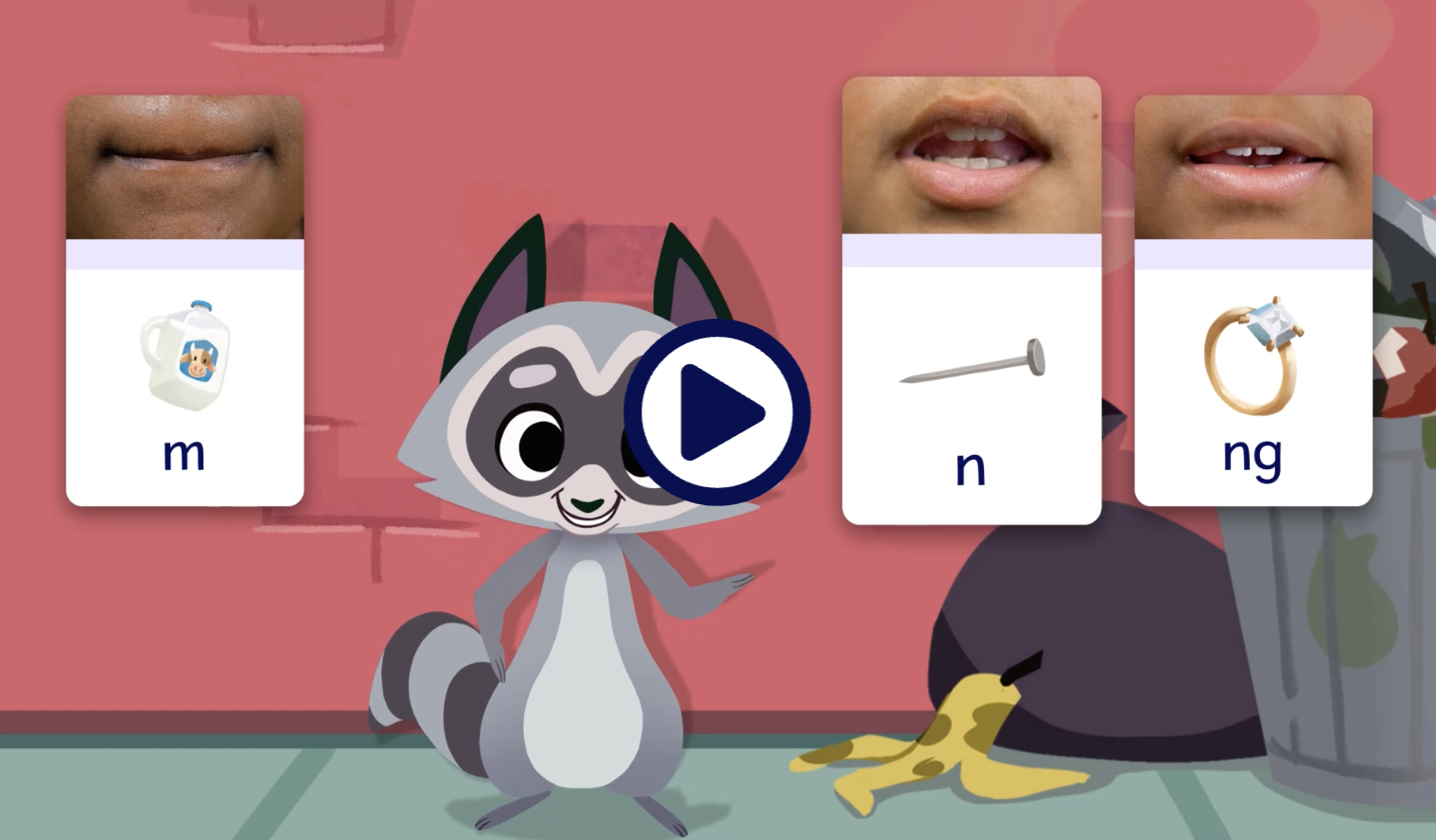

Click the video below to see how nasal sounds are introduced to students.

Understanding these principles of articulation will help draw students’ attention to how they produce the sounds as they practice and build metacognition of articulation, thus laying a stronger foundation for students to later orthographically map the sound to print.

Check out an example of the Sound City virtual software to learn more about how to support kid-friendly language.

Consonant phonemes include both voiced and unvoiced sounds. However, vowels are all voiced, meaning they are produced when the vocal cords vibrate. Which vowel phonemes you introduce first is dependent on your students’ grade level. Vowel Valley on the Sound Wall is organized by the mouth placement, starting with Smile Slope, where the long e sound is made with a smile. As we go down the slope, our mouths gradually open with each vowel phoneme until we reach the bottom of Smile Slope, where our jaws are dropped and our mouths are open to create the short o phoneme /o/. As we ascend Circle Path, our jaws and lips gradually close until we reach Sip it Shack, where our lips are shaped as if we were sipping out of a straw to produce the phonemes /oo/ and /yoo/. Again, we start with the speech sound, which becomes the anchor, and the placement and manner of articulation are how our brains recognize the sounds. From there, students’ brains are primed to bolt each grapheme to its corresponding sound.

Quick Sound Wall Tip

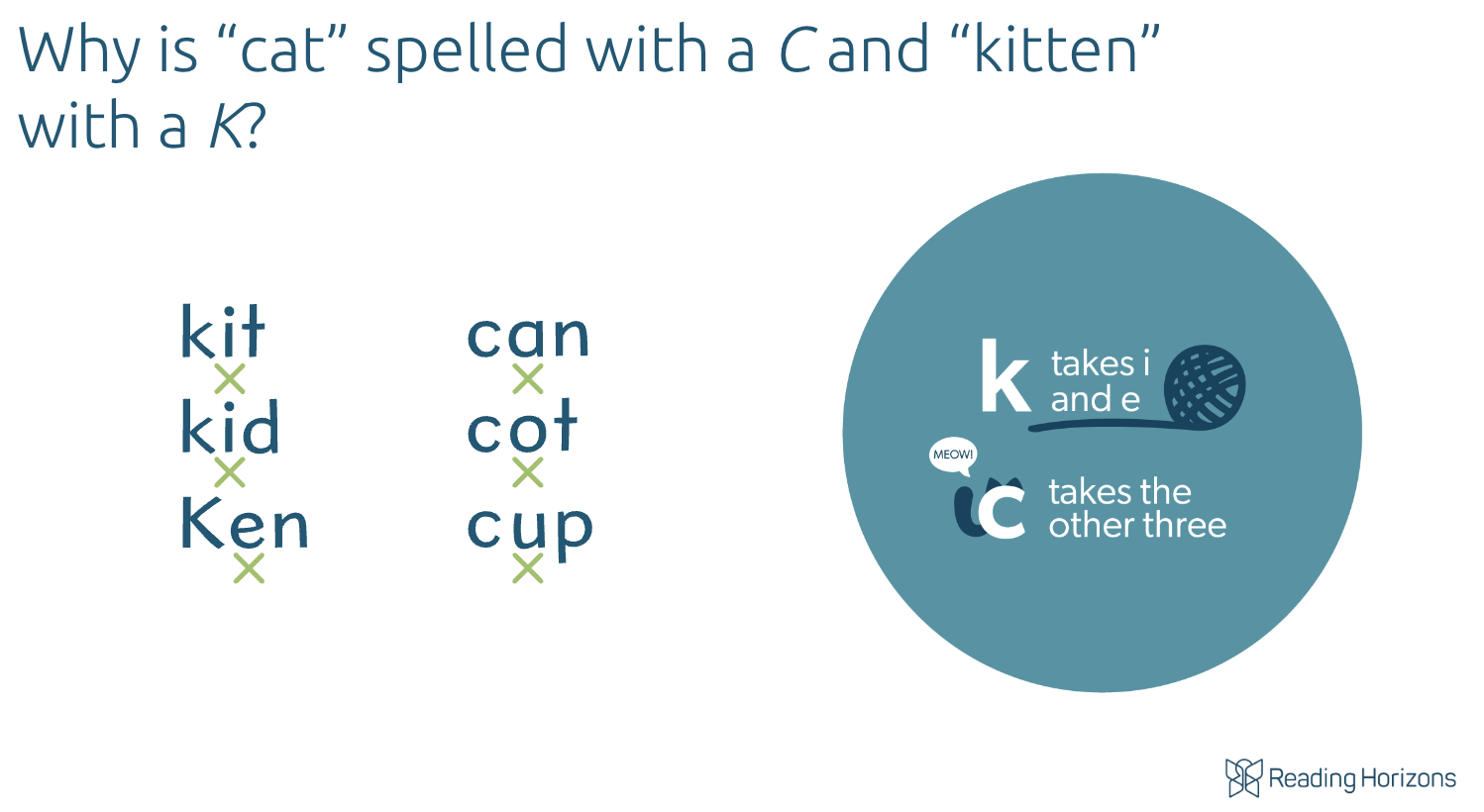

Most sounds are represented by multiple graphemes depending on the spelling patterns in the words in which they are heard. For example, the /k/ sound can be represented by the graphemes c, k, -ck, depending on the orthographic and phonemic structure of the word (e.g., the phoneme /k/ is spelled with –ck when it is heard at the end of a single-syllable word following a short vowel sound like in the word luck). Initially, graphemes are introduced by their most common grapheme-phoneme correspondence. Then, through high-quality phonics instruction, students are taught how letter patterns function in words. As these letter patterns are introduced from simple to more complex, sounds can be revisited to align with the phonics scope and sequence to attach less common graphemes. Sticky notes can be used to cover the graphemes that have not been introduced in the phonics scope and sequence to help students focus on the target graphemes. As new graphemes are introduced, the sticky notes can be removed. In this way, a sound-spelling wall creates a visual artifact of what students have learned in class. Digital sound walls can also be used to show each student the progress they have made individually.

How Sound Walls Become Sound-Spelling Walls

Connecting sound wall instruction to phonics instruction teaches students the skills they need to learn when to use specific graphemes in words. For example, the C/K Spelling Rule taught in phonics instruction teaches that when spelling a word that starts with the /k/ sound, the vowel sound that comes after the /k/ determines which spelling will be used to represent /k/: c or k.

When /k/ precedes sounds spelled with an i, e, or y (e.g., /i/ as in kit), /k/ is spelled with a k. C is used to represent the /k/ sound when it precedes sounds spelled with a, o, and u (e.g., /a/ as in cat). This rule almost always works, except with some proper nouns (e.g., the names Kate, Katherine, Kaitlyn) and words of foreign origin (e.g., kayak, Hong Kong, koala, kangaroo, kung fu).

Additionally, students are explicitly taught that when you hear a /k/ directly following a short vowel at the end of a one-syllable word, it will be spelled –ck. It is more efficient to start with the sounds first and then move to the graphemes. This makes it easier for students to store these spelling patterns in long-term memory, making them available for automatic retrieval when students are reading and spelling.

Once students have heard the targeted phoneme during instruction, they can get out their mirrors and look at the shape of their mouths and tongues as they make the sound and discuss how the sound is produced with the class. Students can compare the shape of their mouth with the associated picture on the classroom sound wall. The sticky note can then be removed to reveal the letter(s) that represents the focus sound so students can make the connection between the sound and its spelling(s). The sound wall lesson is an effective and quick 5 to 10-minute start to phonics instruction.