As a kid, school is your life. You spend more time there than in any other setting except your home (if that). For many students, school gives them a sense of purpose and self-esteem. But, for some, school is like punching a time clock at a miserable job they hate every day.

At the 2019 ASCD Conference in Chicago, Illinois, Donell Pons, M.Ed., MAT, and Laura Axtell, M.Ed., shared a presentation titled Translating Reading Science into Reading Success. During the presentation, Pons shared that on her honeymoon, her husband revealed that he had struggled with reading his whole life. As they discussed his difficulty over the next few weeks, he admitted that as early as first grade he felt doomed to fail at anything connected to school. He didn’t expect to experience any success in the setting he was then just beginning. His story isn’t an isolated case. In his own family, he was surrounded by others who shared his same struggle. And, to a varying degree, an estimated 40 percent of all students face the same difficulty.

In reference to the estimated 40 percent of students who are likely to struggle with reading to at least some degree, reading researcher Dr. Louisa Moats said, “How these students ultimately fare as readers is profoundly affected by the reading programs they are subjected to.”

Students don’t choose how they are taught to read. They are subjected to the method that their teacher was taught or has available. If the program is not research-based, a student who is at-risk for reading difficulties could struggle forever; if it is aligned to research-based best practices, a student may never know he/she was at-risk in the first place.

So, what does this mean? How do we help the 40 percent of students who are dreading the thought of facing the classroom each day? In their presentation, Pons shared what reading science reveals about reading difficulties and effective reading interventions; Axtell shared how to translate the science into practical reading instruction for the classroom. Here are a few rules you can apply to your reading curriculum to make sure it meets the needs of all of your students. Of course, you’re also welcome to skip straight to the full presentation: Translating Reading Science Into Reading Success.

What does reading science reveal about reading difficulties and effective reading interventions?

In order to help struggling readers, you have to understand where they are coming from. You have to know how to recognize warning signs, what might trigger an emotional response, and what is simply not true about their situation.

Rule 1: An estimated 40 percent of all students will struggle with reading

In general, most people naturally learn to speak their native tongue. Our brains are wired for spoken language. Written language, on the other hand, uses a man-made code that must be learned. As mentioned before, about 60 percent of students are predisposed to pick up written language fairly easily; however, 40 percent of students have different brain patterns that prevent them from easily learning to read. Students who are predisposed to struggle with reading require really good reading instruction to become proficient readers. Luckily, really good instruction is beneficial for 100 percent of your students.

Rule 2: Reading difficulties aren’t manifested universally

There are several different brain patterns that result in reading difficulties. Reading difficulties also vary on a continuum from mild to severe. When working with a student who struggles with reading, you must respond to reading assessments and observations to address the unique gaps in their reading skills.

Rule 3: IQ is not connected to reading ability

A student with a low IQ can learn to read fairly easily, and a student with a high IQ can struggle with reading. It is crucial that struggling students don’t associate their intelligence with their reading abilities as this will have devastating effects on their self-esteem that will make reading success more difficult to achieve.

Rule 4: Dyslexia is highly underdiagnosed

It is common for a student to struggle with reading their whole life and never know why they had such difficulty, with dyslexia often being the unknown source of that difficulty. By screening students for dyslexia and referring at-risk students to licensed professionals for formal diagnosis, you can help students understand themselves and their difficulties.

Try this free online dyslexia screener ›

Rule 5: There are three primary characteristics of dyslexia

By knowing the key characteristics of dyslexia, teachers can quickly recognize when dyslexia may be the cause of a student’s reading difficulties. Here are the three key characteristics:

- Family history of reading/learning difficulties (genetic component)

- Difficulty identifying or producing the individual sounds of speech

- Difficulty with rapid automatic naming (RAN)/recall of known letters and sounds

Rule 6: Look to the past

Because reading problems (especially dyslexia) are heritable, to effectively identify what is causing reading difficulties and to best address a student’s needs, we have to look at the full picture. One of the most important parts of a medical diagnosis is looking at a patient’s family history; we likewise need to do that to an extent to best understand our students’ needs.

Rule 7: Reading instruction should be explicit, systematic, and sequential

According to the National Reading Panel, word recognition should be taught in the following ways:

- Explicitly taught by the teacher

- Systematically planned and organized

- Sequenced in a fashion that moves from simple to complex

Rule 8: Reading instruction should include five key components

The National Reading Panel also recommends that reading instruction should include the following components:

- Phonemic Awareness

- Phonics

- Fluency

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

How can you translate reading science into practical instruction for the classroom?

When we understand that many of our students will naturally struggle with reading, we understand that we need to provide reading instruction that will make learning to read more natural and less painful for these students. Here are a few more rules that make reading instruction more accessible to at-risk students.

Rule 9: Start at the very beginning

Regardless of a student’s age, if a student cannot automatically recognize the sounds of the English language, that is where reading instruction needs to start. Students must master the sounds of the spoken language in order to learn to read them. After students can verbally recognize and differentiate each sound, help students map those sounds to letters.

“The biggest mistake we make is when we think that children or adults are ‘too old’ or ‘beyond’ phonemic awareness. If they don’t have phonemic proficiency (instant access to the phonemes in spoken words without even thinking about it), which is pretty well developed in typical readers by third grade, then that is a skill that needs to be addressed or else we have no reason to expect any substantial improvements in word-level reading.” – Dr. David Kilpatrick

Rule 10: Use a logical sequence when teaching letters and sounds

Just because we all learned the alphabet by learning a catchy tune doesn’t mean it’s the most logical sequence to use to teach our students. There are letters that quickly create confusion for students. For example, the vowels e and i have very similar short vowel sounds. These letters should be separated during instruction. Students should be taught to master e before learning i.

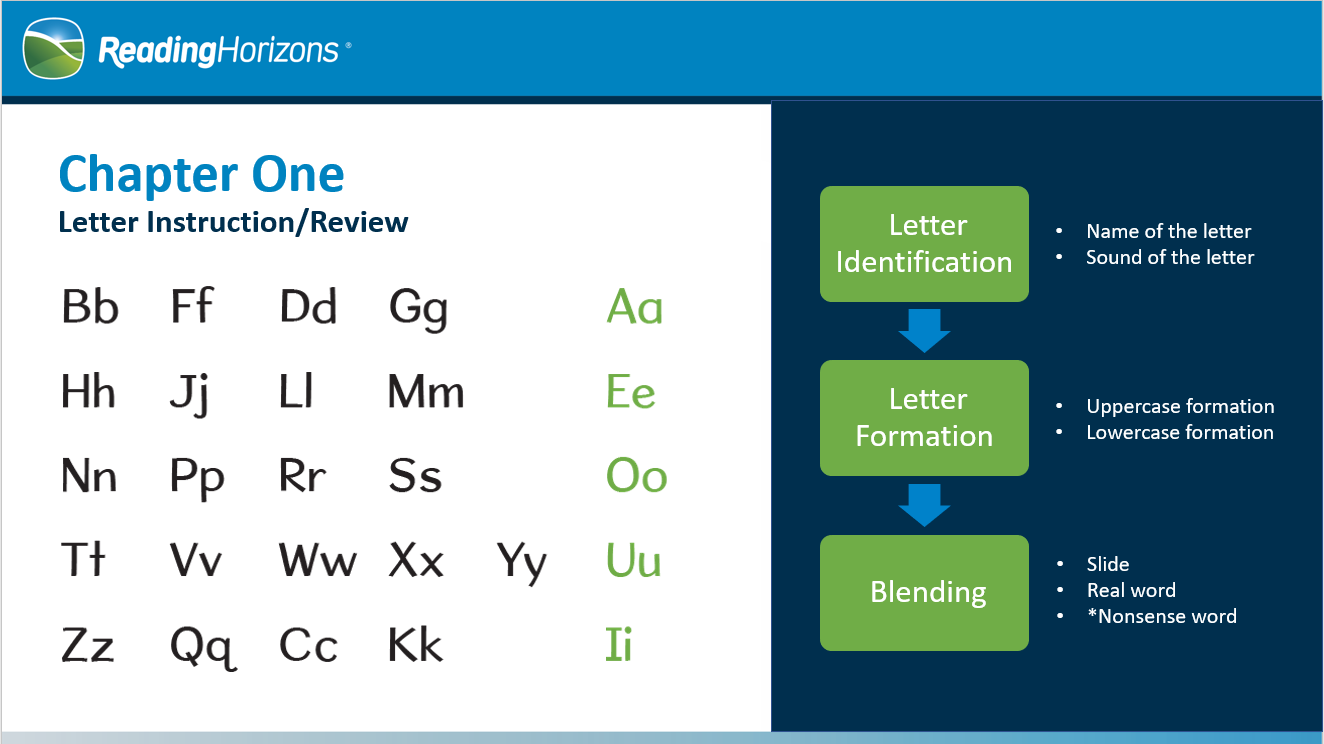

Here is an example of a deliberately sequenced alphabet for minimizing student confusion:

Rule 11: Teach letter and word directionality

Students need to be taught directionality when learning letters. Otherwise, lowercase b and d and p and q are the exact same shape and students will easily mix them up. Students need to be taught specific strategies for differentiating similar letters. Younger students also need to be explicitly taught to read from left to right. Drawing an arrow under basic letter combinations is beneficial as students start to learn or are struggling with letter and word directionality.

Rule 12: Teach the building blocks of English

Once we learn a pattern, our brains are hardwired to look for that pattern. Teach your students how to recognize common letter patterns (Blends, Digraphs, Special Vowel Combinations) and how they alter the pronunciation and spelling of words. By giving students a symbol to connect to a pattern (putting an x under a vowel or arcing a Blend), that pattern becomes even easier to recognize. We can ensure students have mastered a pattern by using nonsense words that follow a pattern to test a student’s understanding by removing their reliance on word memorization. Once a student has mastered a pattern, vocabulary and spelling lists should consist of words that match that pattern.

Learn more about these letter patterns ›

Rule 13: Vowels are the key to pronunciation

There are specific rules that apply to the majority of English words that dramatically help students improve their ability to read, spell, and pronounce unfamiliar words:

- Each syllable only has one vowel or vowel sound

- What comes after the vowel determines how the vowel is pronounced (short or long)

- True Blends generally move together in syllabication

- The Schwa vowel sound

Learn more rules about vowel sounds and syllabication ›

Rule 14: Kinesthetic instruction is not the same as multisensory instruction

Kinesthetic instruction that crosses the midline or involves tactile activities like tapping or writing in the sand may help engage your students; however, it does not qualify as multisensory instruction in and of itself. Multisensory reading instruction combines visual, auditory, and kinesthetic cues to forge new connections in the brain that allow students to process information more quickly. Kinesthetic instruction can be fun, but true multisensory instruction rewires the brain.

Here is an example of a process that engages students in true multisensory instruction:

Rule 15: Start with the rule, not the exception

Although there are exceptions to phonics-based skills, the rules apply to the majority of English words. By teaching the rules, we give students access to the written word more quickly than if we don’t teach the rules or if we focus on exceptions. To reduce student confusion, we should lead with the rules. When students recognize exceptions before reaching that point in your instructional sequence, simply say, “You’re right. We’re going to learn about that exception later on.” Once students have mastered the rules, most exceptions can be explained by looking at the origin of a word.

Rule 16: Teach students to transfer decoding skills into fluent reading

As students learn new letter patterns and phonics skills, we must give them opportunities to transfer these skills to connected text. The text we use to transfer decoding skills to fluent reading should use controlled text that matches what they’ve been taught and that emphasizes the pattern they have just learned. Think of this type of practice as “text with training wheels.”

Rule 17: Protect students that have learning differences

No matter how effective your reading curriculum is, there will always be students that need more time with reading tasks. We have to do what we can to protect these students so school is as safe and successful for them as possible. We need to be sure students have the appropriate 504 Plan or IEP to protect them in the classroom.