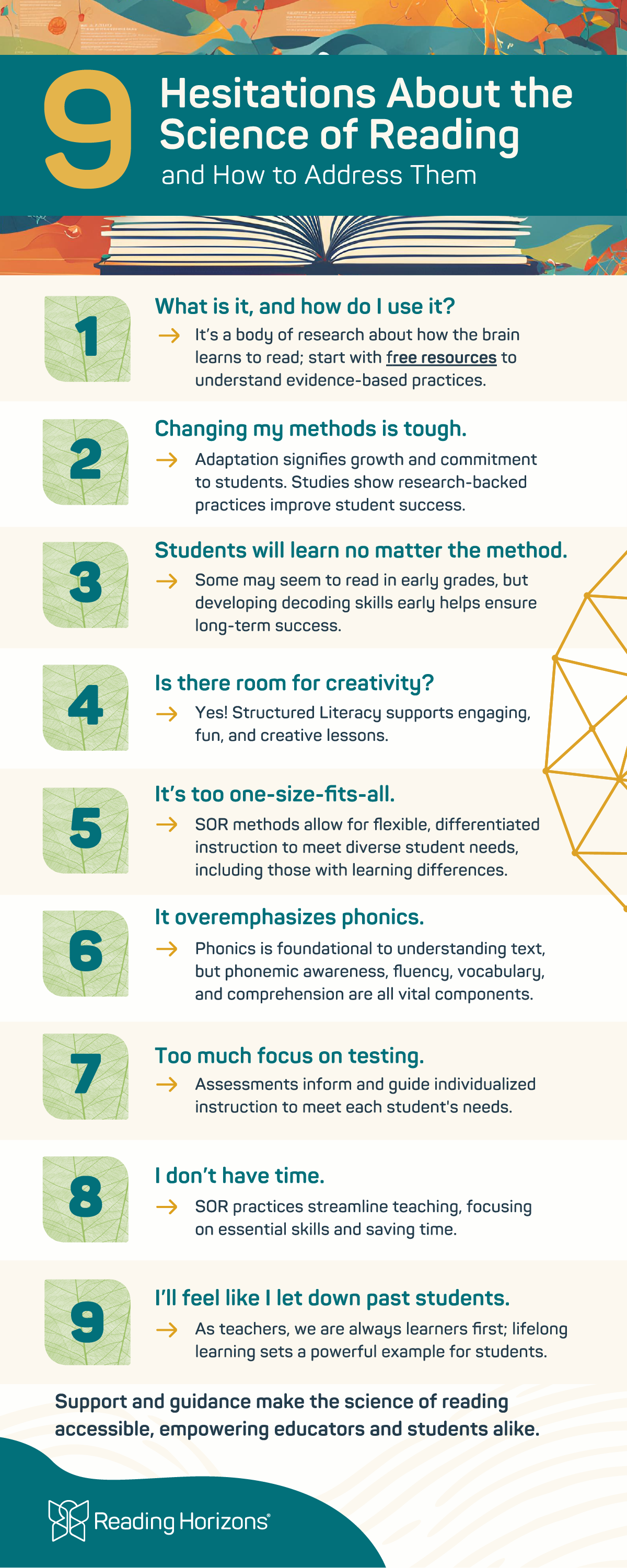

The science of reading is a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing. (TRL, 2021) While it is grounded in extensive studies across psychology, neuroscience, and education, some educators express hesitations about applying evidence-based practices.

Here are nine things educators might say about the science of reading and how to address their concerns.

Download the free infographic below!

1. “I don’t know what the science of reading is or how to apply it.”

Many educators are unaware of the latest findings in the science of reading or may not understand how to apply this research in the classroom.

How to address it:

You are not alone. Many people are unaware of the science of reading or misunderstand its definition. It is an interdisciplinary body of research on how the brain learns to read. Many free resources can help you understand evidence-based practices identified by the science of reading.

The SOR 101 course in The Science of Reading Collective is a great, free starting point!

2. “Changing how I’ve been teaching for years will be hard.”

Teachers often rely on methods they’ve used for years, feeling comfortable with familiar curricula and instructional strategies.

How to address it:

Embracing new, research-backed approaches can enhance student outcomes. Adaptation signifies growth and a commitment to providing the best education based on current evidence. Study after study shows that student success odds improve dramatically with instruction grounded in the science of reading.

3. “Most students will learn to read no matter the approach.”

Many educators in K–3 classrooms favor balanced literacy or whole language approaches because it seems like students are reading. In reality, they only have a relatively small set of words memorized and use pictures and context to guess unknown words.

How to address it:

It’s challenging to initiate change when problems aren’t yet visible; balanced literacy can seem effective in early grades because students appear to read by memorizing words and guessing from context, masking a lack of essential decoding skills needed later. As Emily Hanford highlights in At a Loss for Words, this leads to the fourth-grade “Plateau Effect” (Jean Chall), so we must develop decoding skills early to ensure long-term success.

4. “There’s no room for creativity with the science of reading.”

Some teachers worry that systematic instruction may be too rigid, stifling creativity and student engagement.

How to address it:

The science of reading doesn’t exclude fostering a love for reading or having fun in lessons. Structured Literacy approaches provide a framework to implement engaging, interactive practices that promote creativity while ensuring students acquire essential reading skills.

Check out these games in The Science of Reading Collective!

5. “The science of reading is too one-size-fits-all.”

Some educators believe it promotes a rigid, standardized method that doesn’t cater to the needs of individual students.

How to address it:

The science of reading provides evidence-based practices that teachers can adapt. While it emphasizes certain instructional methods, it encourages differentiation to meet diverse student needs, including those with learning differences.

6. “There is too much emphasis on phonics.”

Some feel that the science of reading places excessive emphasis on phonics instruction, potentially neglecting other crucial literacy components like comprehension, vocabulary, and student motivation.

How to address it:

The science of reading advocates for the five pillars of reading instruction—phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Phonics is emphasized because decoding is foundational for understanding text.

7. “There is too much time spent on testing and not enough on learning.”

A focus on test scores can make teachers hesitant to adopt new methods that they fear may not yield immediate results.

How to address it:

Diagnostics are key to Structured Literacy instruction, as they guide individualized instruction to meet each student’s needs. Assessment is not done for the sake of assessment but rather to inform instruction. Learning happens best when there is a foundation on which to anchor new information; thus, we must assess to ensure that mastery has taken place.

8. “I don’t have time to implement the science of reading.”

Teachers may feel pressured by tight schedules and extensive curricula, leaving little room to integrate new methods.

How to address it:

Integrating the science of reading can streamline instruction by focusing on essential skills, ultimately saving time and enhancing learning efficiency.

9. “Changing how I teach makes me feel like I let down my past students.”

Educators may feel that moving away from their established methods undermines their professional identity and past efforts.

How to address it:

As teachers, we are always learners first. Part of learning is applying what you have learned, just like we would expect our students to do. Modeling lifelong learning for our students is one of the greatest gifts we can give them.

When leaders understand and address the hesitations around the science of reading, they pave the way for educators to embrace evidence-based reading instruction confidently. This support ultimately leads to better literacy outcomes, creating a bright future where every student has the opportunity to succeed.