As the smells of sunscreen and chlorine start to give way to the smells of new textbooks and freshly sharpened pencils, teachers are shifting their focus to planning for the new school year. The schools I am working with are bringing in new reading programs that are attempting to cover all the areas of the English Language Arts Standards. While I understand the desire to go for the one-size-fits-all approach, doing so may lull educators into a false sense of security that they are covered standards, when in reality, if they are not careful, this will perpetuate the very problem many standards are trying to remedy.

Louisa Moats, Ph.D., an internationally recognized reading expert, recently recorded a podcast that seeks to merge what we know about effective reading practices with the Common Core State Standards. In the podcast, she addresses the very same concerns I have heard educators raise in my work with their schools. She points out that a distinction needs to be made between the views and values of traditional English Language Arts/traditional English teaching and the vocabulary and concepts needed for teaching developmental reading and writing. The standards are focused on more enriched reading and writing—which is needed, but Moats’ concern is that there is no real evidence that more information-based or difficult text is beneficial in reading instruction. She states that while the literary elements are key, so are the tools for teaching reading. Before we overwhelm students with difficult text, we may need to focus on the sequential presentation of practice opportunities for the specific skills being taught.

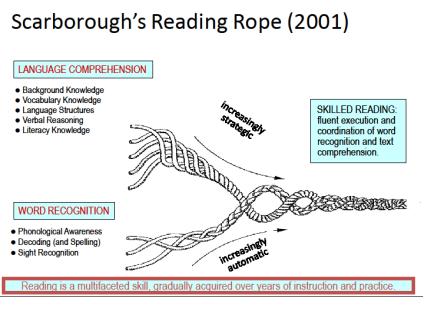

Moats suggests using Scarborough’s Reading Rope to help us understand the reading development process and to illustrate how skilled reading develops over time. This image shows what we call the simple view of reading: both language comprehension strands and word recognition strands are necessary for skilled reading. If students are missing strength or proficiency in any one of these strands of the reading rope, it is likely that their reading proficiency will suffer. The image also reveals, however, that word recognition skills are developed quite separately at the beginning of the process. They need to be built up very deliberately and specifically so that they can serve the purpose of supporting and being integrated with all of the other strands of the rope.

Moats suggests using Scarborough’s Reading Rope to help us understand the reading development process and to illustrate how skilled reading develops over time. This image shows what we call the simple view of reading: both language comprehension strands and word recognition strands are necessary for skilled reading. If students are missing strength or proficiency in any one of these strands of the reading rope, it is likely that their reading proficiency will suffer. The image also reveals, however, that word recognition skills are developed quite separately at the beginning of the process. They need to be built up very deliberately and specifically so that they can serve the purpose of supporting and being integrated with all of the other strands of the rope.

The programs being created to cover the CCSS fall short overall because they focus more on the comprehension piece than the decoding piece. In these programs, phonics skills are not taught as explicitly or sequentially as research prescribes (an explicit, sequential approach is most effective); and the pieces of word recognition and language comprehension are not kept separate and deliberate in the beginning, as Moats advises, to ensure the coordination of those skills in the end. If the schools implementing these all-inclusive programs use only the phonics piece that comes with the programs, students will be shortchanged yet again.