This blog post combines tips from three experts as expressed on Podclassed—a podcast sponsored by Reading Horizons. The experts include Jim Wright, trainer, consultant, and creator of the Intervention Central website; Dr. Douglas Fuchs, Professor at Vanderbilt University; and Lynn Hobratschk, Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Curriculum and Instruction at Friendswood ISD in Texas. You can listen to their full interviews from this two-part episode at the following links:

Part 1: Is Response to Intervention (RTI) Really the Road to Improvement?

Part 2: Is Response to Intervention (RTI) Really the Road to Improvement?

With research highlighting potential pitfalls in the Response to Intervention (RTI) Model, top experts in the field provide tips for avoiding an ineffective implementation and how to meet the original goal of the RTI model. That goal is to provide intervention as early as possible rather than waiting for students to fail before giving additional instructional support.

With research highlighting potential pitfalls in the Response to Intervention (RTI) Model, top experts in the field provide tips for avoiding an ineffective implementation and how to meet the original goal of the RTI model. That goal is to provide intervention as early as possible rather than waiting for students to fail before giving additional instructional support.

Before delving into the solutions, let’s look at a few of the problems our expert panel pointed out that have led many RTI programs to perform poorly:

- Overcomplicated implementations try and do too much at a time.

- RTI is mandated without funding and other competing initiatives that make it easy to become an afterthought.

- Many tier II and III interventions aren’t carried out by qualified educators.

- There isn’t enough capacity in tier II and III interventions.

Luckily, an RTI program can be implemented to maximize student success with the right approach.

Here are the key tips that our panel of experts highlighted as remedies to these challenges:

Start with data.

When an RTI program isn’t based on data, students end up being selected for interventions based on having the loudest parent or teacher rather than need. At Friendswood ISD in Texas, the RTI committee chose a handful of assessments and defined specific data points for each tier, so student priority wasn’t based on conjecture. They also looked at the results of each assessment and assigned results a red, yellow, or green classification. If a student’s assessment results were assigned a red for multiple assessments, then that was a clear sign they needed an intervention. If a student was only assigned red on one assessment, but the others were yellow or green, the general education classroom teacher would work with the interventionist to address the student’s needs in the classroom.

These data reviews were held with all teachers of a grade level. This way, the teachers would get a big picture of all students’ needs in their grade level. Thus, they were more compliant if a student in a different classroom got support over one of the students they were worried about because they could see that the data pointed to this decision. This also shifted the perspective among teachers from “my students” to “our students.”

RTI needs to be a way of thinking, not a checkmark.

According to Jim Wright, the creator of Intervention Central, one of the biggest indicators that an RTI implementation will be successful is whether or not the school principal is on board. If RTI doesn’t permeate the entire school culture and how they solve problems, it’s hard for it to be effective, and it’s not likely to stick around. It becomes a checkmark rather than a paradigm shift.

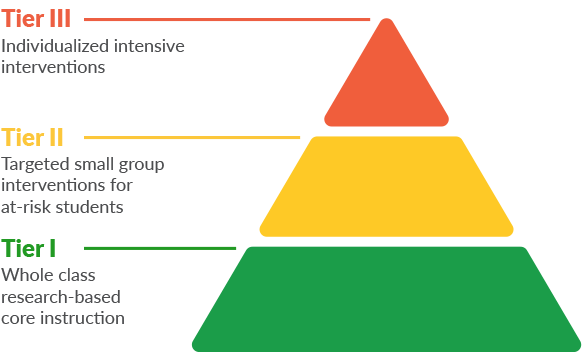

You don’t have to use a three-tiered model.

Dr. Douglas Fuchs of Vanderbilt University points out that RTI doesn’t have to be the classic three-tiered pyramid. Some schools could benefit from a more ambitious four-tiered model, while others benefit from a simpler two-tiered model. In theory, he believes more tiers are better, but depending on the school’s background and how long they’ve been implementing RTI determines whether more tiers are beneficial in practice. Suppose a school is starting to implement RTI for the first time. In that case, a two-tiered model can be more effective because they can work on solidifying the first two tiers—which can take a significant amount of time and effort—before layering in additional levels. A school with an established RTI program functioning well could greatly benefit from adding a fourth or even a fifth tier.

Make movement between RTI tiers fluid.

The expert panel also suggested that schools pull data frequently to decide which students will enter and exit each tier throughout the school year. This allows schools to build a higher capacity for available interventions because students don’t get stuck in a tier. By periodically assessing students to determine progress and needs, you can open up spots for kids showing emerging needs.

Have a three to five-year implementation plan.

Don’t try and do everything at once, but have a plan for where you want to go. If a school tries to do too much at one time, then an RTI model is unlikely to yield positive results. However, schools do need to sketch out a plan to have a vision for how they want the program to grow and develop. By mapping out how the implementation will roll out over three to five years, you don’t overwhelm staff, and everyone can work together to build the program strategically.

Here are a few tips for making each RTI tier more effective:

Tier I: Core Instruction

Start with tier I.

If you have a weak tier I, the other tiers will get overloaded, and the system won’t be able to fulfill its goals. Tier II and III can only be effective if tier I is effective. Tier I affects every student—so get that tier operating first. Regardless of the use of an RTI model or not, a strong tier I is crucial for every school because every school should have the goal of effectively teaching their students. Strong interventions in tier II and III don’t fix weak instruction in tier I. Tier I instruction has to be solid. We need to train teachers, be selective in our programs, and carefully watch the results.

If tier I isn’t effective for about 80 percent of all students, something needs to change.

If tier I isn’t yielding results for most of your students, additional teacher training or a new evidence-based reading curriculum needs to be implemented. Research has found that students consistently perform the best in reading when taught explicit phonics (Structured Literacy). Having many students move to tier II doesn’t mean students are failing. It means changes need to be made to instruction or the reading curriculum.

Tier II: Targeted Intervention

- Review student placement every six to eight weeks, and use a different intervention if a student isn’t showing progress after this time frame.

- If students don’t make progress after two sessions (one session being six to eight weeks) in tier II, move the student to tier III.

- Have certified educators lead interventions and use paraprofessionals for repetitive student practice.

- Start students at lighter interventions until they show additional need to keep the capacity open in the more intensive interventions.

Tier III: Intensive Intervention

- Use problem-solving teams to cater instruction to each student’s needs.

- If more than 5 percent of students are being referred to tier III, something needs to change in tier I or II: additional teacher training, different interventions, etc.

- Tier III is not special education; special education should be a separate system.

- If a student doesn’t show progress in tier III with one-on-one instruction, the student might need to get a formal diagnosis to look for learning disabilities. The student may potentially need to be moved into the special education program.

Conclusion

Implementation makes or breaks an RTI program. When a school commits to implementing an RTI program and designs it to rely on data and to permeate the school’s culture, the program is likely to be effective. What challenges or solutions have you seen as you’ve worked to implement an RTI program in your school? What tips would you add? Share in the comment section.

Meet the Experts

Jim Wright is a national trainer and consultant to schools and organizations on Response to Intervention/Multi-Tier System of Supports and other issues relating to educational change and at-risk learners. He is also a certified school psychologist and administrator with over 17 years of experience working in public schools in central New York State. Jim is the creator of Intervention Central (www.interventioncentral.org).

Dr. Douglas Fuchs is Professor and Nicholas Hobbs Chair in Special Education and Human Development and a member of the Vanderbilt-Kennedy Center. Before joining the Vanderbilt faculty in 1985, Fuchs worked as a teacher and school psychologist. At Vanderbilt, he has been the principal investigator of 50 federally-sponsored research grants. Fuchs is the author or co-author of more than 300 articles in peer-reviewed journals and 60 book chapters.

Lynn Hobratschk is the Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Curriculum and Instruction at Friendswood ISD in Texas.